4)

In its 1993 report on Indonesia’s energy and environment the World Bank found that: ...for Indonesia, as with most other developing countries in Asia, the role of nuclear in its total energy supply needs to be reviewed with care, due to: (i) the availability of less expensive alternative, such as gas and coal; (ii) the shortage of investment capital; and (iii) concerns with the feasibility of evacuation plans in densely populated areas, seismic, volcanic and soil conditions, and the availability of cooling water in many areas of Java, where the potential market is located

(World Bank 1993: 38).

ENERGY ALTERNATIVES

Indonesia’s non-nuclear energy resources

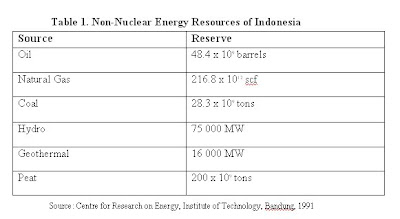

The feasibility study by NEWJEC Inc., of the first nuclear power plant site at the Mt Muria Peninsula area, includes an evaluation of Indonesia’s other energy resources. Non-nuclear energy resources in Indonesia such as coal, oil, natural gas, hydro, geothermal and peat are substantial. The figures used in this section for energy resources other than peat are taken from the 1993 revised version of the Feasibility Study of the First Nuclear Power Plants at Muria Peninsula Region produced by NEWJEC.

There are vast reserves of coal in Indonesia, which is in direct competition with nuclear power. The proven reserves are approximately 4.8 billion tons and with probable reserves totalling 18.8 billion tons. In addition, geological potential indicates that a further 10.7 billion tons of coal resource is available. At a production rate of 10.6 million tons per year,55 the coal reserves would last for another 350 years. The major reserves are located on Sumatra and Kalimantan, with some smaller ones on Java, Sulawesi and Irian Jaya. However, as NEWJEC points out, only 35% is classified as sub bituminous and bituminous as well as anthracite; the remaining 65% is lignite, which has a lower calorific value and a higher moisture content (Task No.2: 6). When all the royalty and corporation taxes have been added on, the average production cost of Indonesian coal is estimated to be approximately US $ 30-60 per ton (Task No.2: 7), which still makes coal more economical than nuclear energy.

cycles of over 50%, and in combined cycles, such as a chemically recuperative

cycle, efficiencies are over 60%.... Thus natural gas is a strong competitor, and,

incorrectly I think, it has the support of the environmental movement (King 1993: 202).

By 1993 Indonesia’s proved oil reserves amounted to 5.3 billion barrels, or at 1993 production rates, equivalent to a reserves to production ratio of 10 years. In addition, Indonesia could convert 5.4 billion barrels of probable oil reserves by intensive geological exploration. The so called frontier areas are suspected to contain another 37.4 billion barrel of oil. NEWJEC argues that high risk exploration and intensive capital investment may be necessary to prove this oil potential (Task No. 2: 1).

The total potential for hydropower in Indonesia is estimated at 75 000 Megawatt (MW). Until 1990 only 3200 MW had been used for electricity generation. Unfortunately, the biggest share of the potential is situated in Irian Jaya and Kalimantan, where there is insufficient demand for electricity to justify large-scale hydropower investment. The heavily populated island of Java has only a total potential of 4500 MW of hydropower, and about half of that has already been tapped.58 NEWJEC argues that the main problem with hydropower in Indonesia is the mismatch between population distribution and the sites where hydropower resources are found (Task No.2: 10-11).

Peat is another substantial energy resource in Indonesia, although not mentioned in the NEWJEC study. The Centre for Research on Energy, Insitute of Technology in Bandung estimated in 1991 that the total energy resource from peat amounted to 200 billion tonnes (See Table 1). And finally, Indonesia’s archipelago has an abundance of wind and sun, as well as wood, animal and vegetable waste (e.g. rice husk). The availability of these renewable resources makes it attractive to consider wind generators, photovoltaic systems and gasifier units for diesel power (Wachjoe 1994: 1), particularly in remote or rural areas where the main electrical grid does not reach, or as a means to reduce pressure on the grid.

Sources: http://wwwarc.murdoch.edu.au/wp/wp65.pdf

0 Responses to 4)

Something to say?